Crossposted from jaspervdj.be

The 12 urenloop is a yearly contest held at Ghent University. The student clubs compete in a 12-hour-long relay race to run as much laps as possible. Each of the 14 teams this year had a baton assigned, so they can only have one runner at any time.

This event is not all about the running – it’s become more of a festival, with lots of things to do and see (I hope I can convince you to check it out if you’re based in Ghent) – but I will focus on the running here, and more specifically: the system used to count the laps.

The manual way

Lap counting used to be done in a manual way – people worked in shifts, with two people counting laps at the same time. Simple touchscreens were used, so they basically just sat next to the circuit, looked at the runners that passed and touched the corresponding buttons on the screen.

Although pretty efficient, a completely automated system would be nice-to-have for several reasons:

- less mistakes are possible (provided it’s a good system);

- fewer people are needed (provided it doesn’t need constant monitoring);

- the data can be used for several real-time visualisations.

So, Zeus WPI, the computer science club I am a committee member of, decided to take on this challenge.

The hardware

Bluetooth

We decided to attach bluetooth dongles to the relay batons. I’m now pretty confident this was a good choice. The other option was the more obvious RFID, but the main problem here was that RFID hardware is ridiculously expensive. Besides, we already had pretty awesome embedded devices we could use as bluetooth receivers.

Gyrid

These bluetooth receivers were borrowed from the CartoGIS, a research group which (among other things) studies technology to track people on events (e.g. festivals) using bluetooth receivers.

The receivers run a custom build of Voyage Linux created to run the Gyrid service. What does this mean for us? We get simple, robust nodes we can use as:

- linux node: we can simply SSH to them and set them up

- switch: to create a more complicated network setup (see later)

- receiver: sending all received bluetooth data to a central computing node

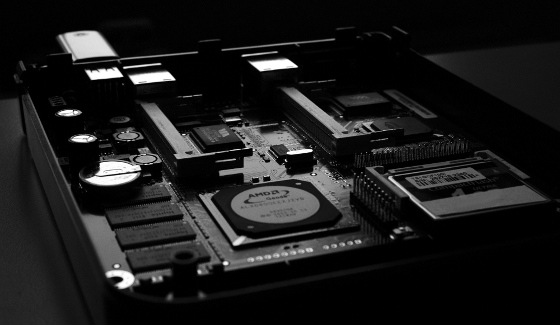

Here is another picture of what’s inside of a node:

Relay batons

We built the relay batons using a simple design: a battery pack consisting of 4 standard AA batteries and connecting them to a bluetooth chip, put in a simple insulation pipe. Some extensive tests on battery duration were also done, and it turns out even the cheapest batteries are good enough to keep a bluetooth chip in an idle state for more than 50 hours. We never actually set up a bluetooth connection between the receivers and the relay batons – we just detect them and use that as an approximate position.

Network setup

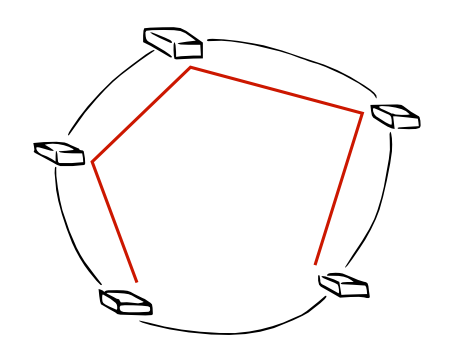

The problem here was that we only could put cables around the circuit, we couldn’t cut right through to the other side of the circuit. This means the commonly used Star network was impossible (well, theoretically it was possible, but we would need a lot of cables). Instead, Jens, Pieter and Toon created an awesome ring-based network, in which each node also acts as a switch (using bridging-utils). Then, the Spanning Tree Protocol is used to determine an optimal network layout, closing one link in the circle to create a tree. This means we didn’t have to use too much cables, and still had the property that one link could go down (physically) without bringing down any nodes: in this case, another tree would be chosen. And if two contiguous links went down, we would only lose one node (obviously, the one in between those two links)!

The software

count-von-count

Now, I will elaborate on the software which interpolates the data received from the Gyrid nodes in order to count laps1. count-von-count is a robust system written in the Haskell programming language.

At this point, we have a central node which receives 4-tuples from the Gyrid nodes:

(Timestamp, Mac receiver, Mac relay baton, RSSI value)

After some initial tests, we concluded the RSSI value was not too useful for us. Later, we did use it to determine if a signal was strong enough (i.e. RSSI above a certain treshold), and then we discarded the RSSI value. This leaves us with a triplet:

(Timestamp, Mac receiver, Mac relay baton)

We do the calculations separately for each team – only we work with relay batons instead of teams. This means that we get, for every team:

(Timestamp, Mac receiver)

We also (hopefully) know the location of our Gyrid nodes, which means we can again map our data to something more simple:

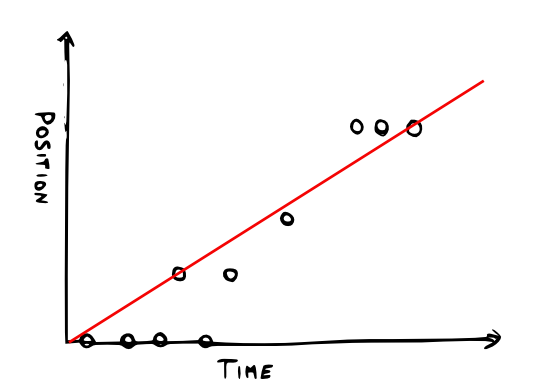

(Timestamp, Position)

This is something we can easily plot. Note that there are only a few possible positions, since we discarded the RSSI values because of reliability issues.

I’ve illustrated the plot further with a linear regression, which is also what count-von-count does. Based on this line, it can figure out the average speed and other values which are then used to “judge” laps. When count-von-count decides a relay baton has made a lap, it will make a REST request to dr.beaker.

dr.beaker

dr.beaker is the scoreboard application. It’s implemented by Thomas as a Java service that runs on top of GlassFish. It provides features such as:

-

registering & managing batons and teams

-

assigning batons to teams

-

a scoreboard

-

a history of the entire competition

and more.

Conclusion

It’s a hardware problem.

When the contest started, both Gyrid, count-von-count and dr.beaker turned out to be quite reliable. However, our relay batons were breaking fast. This simply due to the simple, obvious fact that runners don’t treat your precious hardware with love – they need to be able to quickly pass them. Inevitably, batons will be thrown and dropped.

Initially, we were able to swap the broken relay batons for the few spare ones we had, and then quickfix the broken ones using some duct tape. After about five hours, however, they really started breaking – at a rate that was hard to keep up with using quickfixing.

Hence, this is the main goal for next year: build reliable, solid relay batons. We need to be able to throw them down from a four-story building. Beth Dido needs to be able to use them as a dildo, and they should come out unharmed. Feel free to contact us if you’re interested in making this happen!

-

Because the author of this blogpost is also the author of

count-von-count, this component is explained in a little more detail. ↩